Evaluation of San Diego Small Business Relief Fund

San Diego Skyline

What was the challenge?

The U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA) aims to support small business revenue and job growth and restore small businesses and communities after disasters. SBA is interested in understanding the impact of community-based approaches to help small businesses respond and recover to the COVID-19 pandemic. In March 2020, the City of San Diego used CARES Act funding to create the Small Business Relief Fund (SBRF) to help small businesses affected by the economic fallout from the COVID‐19 pandemic. By December 2020, the city had disbursed nearly 17 million in grants and loans of up to $20,000. Yet demand for funds far exceeded supply: of the roughly 10,500 applications submitted between March 27 and April 14, 2020, funds could only be extended to just over 2,300 businesses. We partnered with the City of San Diego to estimate the effect of funding on business resilience using quasi‐experimental methods to compare the outcomes of those applicants who were and were not funded.

What was the program change?

We aimed to estimate the impact of SBRF funding on business outcomes by combining available sources of data on small businesses. We merged application data with panel data from a business review platform on temporary and permanent business closure, bankruptcy data from the federal bankruptcy court, and consumer credit card transaction data.

Businesses who applied to the SBRF were reviewed for eligibility, and then invited on a first-come-first-served basis to submit documentation for further review and possible funding. Whether and when an invited business receives funds depends on a process OES could not observe: businesses must accept the invitation and return the requested supplementary documents, these must be reviewed by program staff at the City, additional reviews and follow-up may be conducted, then the request for funds needs to be processed through the financial department. Unobserved attributes of the business that might help with completing these steps—for instance, having an on-staff accountant to respond to requests—are likely correlated with the business’s ability to weather the pandemic. A simple comparison of funded to unfunded businesses would therefore be biased.

How did the evaluation work?

To address this issue, we first estimated the effect of being invited to submit documents for funding. While we were unable to predict which businesses would and would not get funded, the application data made it possible to predict, using a collection of machine learning methods, which businesses would be invited, with 95% accuracy. Using those predictions, we created inverse propensity weights, which downweight (upweight) invited businesses with a high (low) probability of being invited, and vice versa for uninvited businesses. In principle, this allows for unbiased estimation of the causal effect of an invitation to submit funding. This estimate is then scaled up by a factor proportional to the rate at which invited businesses were funded, using a procedure called two-stage instrumental variables regression, to estimate the effect of receiving funding among those businesses that would receive funding if they were invited.

What was the impact?

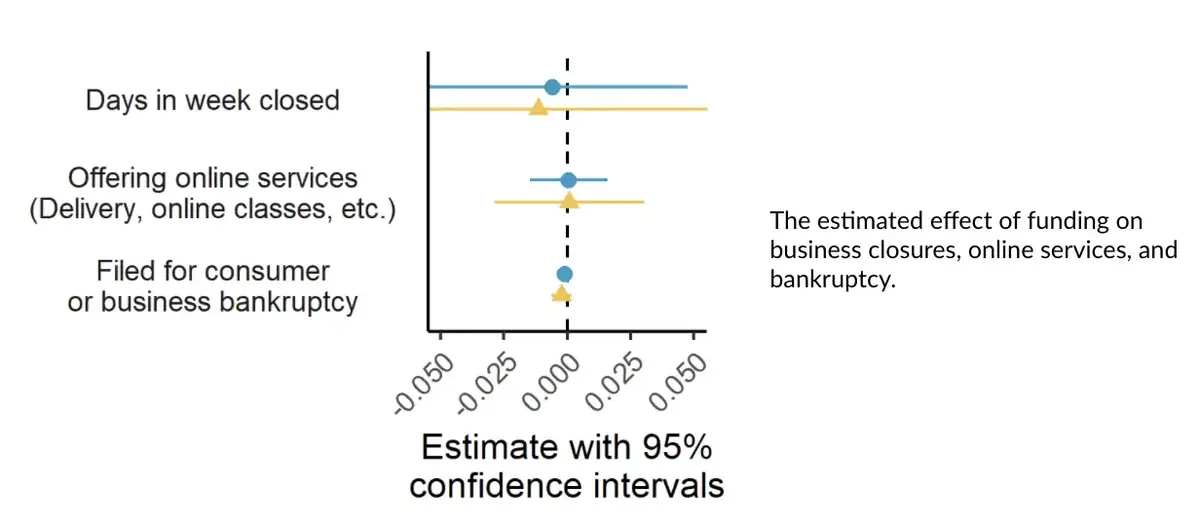

We did not find statistically significant evidence of program impact across any of the main analyses specified in the analysis plan: business closures, provision of online services, and bankruptcy filings (see Figure 1). This should not be mistaken with finding evidence that the program did not work: given the data, we cannot rule out either positive or negative program impacts. The large number of applications suggests business owners saw a great need for the funding. Our inability to say more relates to the statistical uncertainty in our estimates.

Figure 1. The estimated effect of funding on business closures, online services, and bankruptcy

Note: Blue circles show estimated effect of invitation, yellow triangles show estimated effect of funding, among businesses that would receive funding if invited.

The analysis encountered three main challenges. First and foremost, match rates between business application and outcome data were very low. Only 34% of the businesses in the sample had a business rating review platform account at any point; only 11% recorded at least one transaction in the credit card data; and bankruptcy records existed for less than 1% of the sample. Second, the analysis relied on its ability to predict invitation as opposed to funding status. However, only 34% of invited businesses were funded: the others withdrew, did not follow up on invitations, or were found ineligible in subsequent review. Finally, the funding was rolled out in the middle of pandemic lockdowns that may have had a much greater impact on business-owners’ decisions to stay open than the amount of available liquid assets. These challenges greatly limit the inferences that can be drawn from the analysis.

Key takeaways

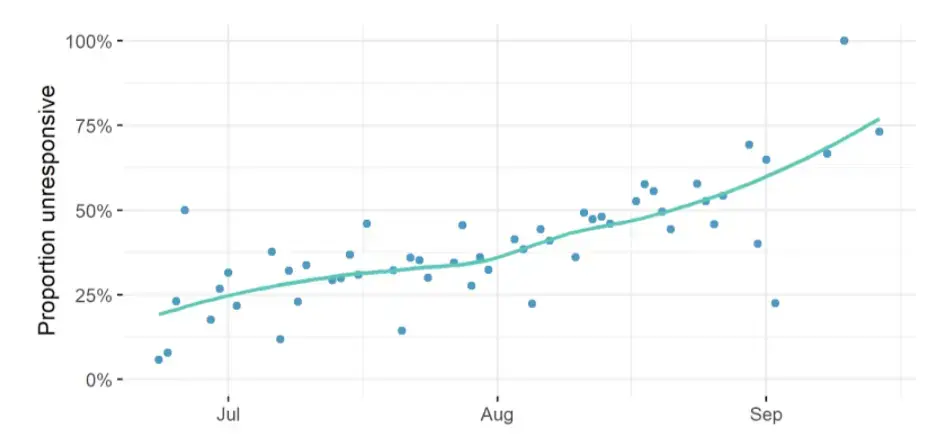

We identified at least two directions for future work to improve both program implementation and evaluation. First, building comprehensive and easily accessible datasets on the small business population. Access to EIN, address, and quarterly wage bill of all of the business establishments in a jurisdiction, could allow outreach to be better targeted and support additional research on employment impacts of relief programs. Second, prioritizing additional evaluation activities on how to increase follow-up by relief applicants. Businesses failing to respond to invitation emails constituted a major challenge for both program implementation and evaluation. Nonresponse seems to be driven by decreasing salience over time (see Figure 2). The probability of not responding to an invitation email increases from less than 25% at the beginning of the email campaign to 75% by its conclusion. This suggests a need to focus on reaching out early during emergencies in order to reach business when they are most likely to respond.

Figure 2. Rate at which business-owners failed to follow up on invitations to submit documents for funding over time

Verify the upload date of our Analysis Plan on GitHub.